Does Alcohol Shorten Your Lifespan? The Honest Truth

By Brent | Last Updated: February 10th, 2026

Does Alcohol Shorten Your Lifespan? The Honest Truth

Key Takeaways

> Heavy drinking dramatically shortens lifespan, often by decades

> Moderate drinking does not extend lifespan and may still accelerate biological aging

> The "red wine is healthy" narrative is largely based on flawed research assumptions

> Alcohol appears to shorten telomeres, a key marker of cellular aging

> Any potential social or psychological benefits come with measurable biological costs

A Question of Moderation

There is little debate that excessive alcohol consumption is harmful. Alcohol use disorder is associated with lifespan reductions of up to 28 years, driven by liver disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and injury.

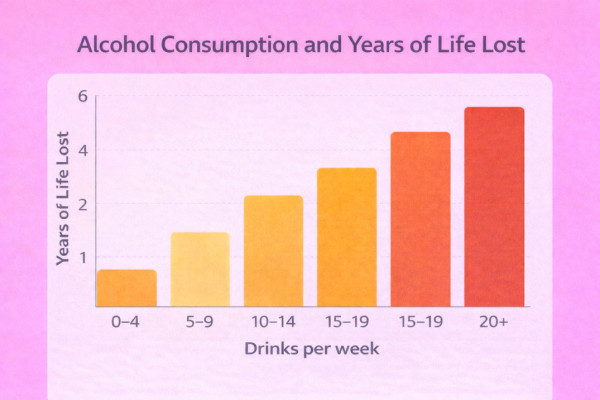

Even lower levels of regular consumption matter. Studies show that drinking 10–15 drinks per week can shorten life expectancy by one to two years, while heavier patterns can reduce lifespan by four to five years or more. The real controversy lies in light-to-moderate drinking, and whether the supposed "longevity benefits" actually exist.

The Red Wine Myth (And Why It Persists)

The idea that alcohol, especially red wine, is good for you traces back to the French Paradox. In the early 1990s, researchers observed low rates of coronary heart disease in France despite high saturated fat intake and attributed the difference to wine consumption.

This conclusion overlooked major confounders: high daily physical activity, smaller portion sizes, different smoking patterns, and inconsistent disease reporting across countries.

A narrow association between wine and heart disease prevention gradually morphed into a sweeping cultural belief that alcohol promotes longevity. That leap was never scientifically justified.

The resveratrol argument doesn't hold up either. You'd need to drink hundreds of glasses of red wine daily to reach the doses used in laboratory studies showing benefit. For those interested in evidence-based interventions, longevity supplements offer far more practical approaches.

What the Latest Research Actually Says

Modern studies correct for many of the flaws in earlier research. When researchers account for prior health status, smoking history, and socioeconomic factors, the supposed longevity advantage of moderate drinkers largely disappears.

Large cohort analyses now conclude that:

> Abstainers often appear less healthy because many stopped drinking due to illness (the "sick quitter" effect)

> Moderate drinkers are often healthier for other reasons, not because of alcohol

> Alcohol should not be recommended for health or longevity

A 2024 Mendelian randomization study published in Scientific Reports found that alcohol consumption decreased lifespan by approximately 1.09 years per logged alcoholic drinks per week, and this effect remained significant even after adjusting for smoking.

In short, alcohol does not meaningfully extend life once bias is removed.

How Alcohol Accelerates Aging

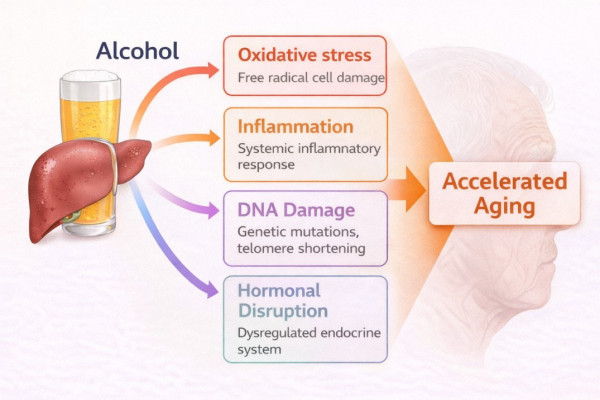

Alcohol affects aging through multiple biological pathways:

Increased oxidative stress: The metabolism of ethanol produces reactive oxygen species that damage cellular structures, contributing to inflammation and accelerating the hallmarks of aging.

Chronic inflammation: Regular alcohol consumption elevates inflammatory markers throughout the body. For those working to beat inflammation, alcohol directly undermines those efforts.

DNA damage: Acetaldehyde, a byproduct of alcohol metabolism, is a known carcinogen that causes direct damage to genetic material.

Hormonal disruption: Alcohol interferes with hormone regulation, affecting everything from sleep quality to metabolic function.

These processes overlap directly with known mechanisms of cellular aging. Alcohol doesn't just increase disease risk; it appears to accelerate the aging process itself at the molecular level.

Telomere Trouble: Alcohol and Biological Aging

Telomeres are protective DNA caps that shorten with age. Faster shortening is associated with higher disease risk and reduced lifespan. They're one of the key markers measured in epigenetic age tests to determine biological age versus chronological age.

Recent genetic studies using Mendelian randomization, a technique that helps establish causality rather than mere correlation, show that alcohol consumption is linked to shorter telomeres, even at moderate intake levels.

Key findings from the 2022 Oxford Population Health study (245,354 participants):

> Drinking more than 29 units weekly was associated with 1–2 years of age-related change in telomere length

> Individuals with alcohol use disorder showed telomere shortening equivalent to 3–6 years of biological aging

> Each increase in weekly alcohol consumption correlates with telomere shortening equivalent to losing roughly one year of life

The biological mechanism appears to involve increased oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant capacity from ethanol metabolism. This suggests alcohol contributes to aging at the cellular level, not just through disease.

For a deeper dive into how telomeres affect your longevity, see our guide on telomere timekeepers and cellular aging.

Is There a "Safe" Amount of Alcohol?

From a longevity perspective, the answer is increasingly uncomfortable.

While very low intake may carry minimal risk, no level of alcohol consumption has been shown to improve lifespan. Even one drink can negatively affect:

> Sleep quality: Alcohol disrupts REM sleep and sleep architecture. For those optimizing sleep for longevity, even moderate drinking undermines recovery. See our guide on sleep optimization for evidence-based alternatives.

> Heart rate variability: A key biomarker of autonomic health that alcohol measurably impairs.

> Recovery metrics: For those using fitness trackers or sleep trackers to optimize health, alcohol's negative impact shows up clearly in the data.

Alcohol may not dramatically shorten life at low doses, but it likely chips away at long-term healthspan. As Dr. Tim Stockwell's research suggests, even two drinks per week may shorten your life by 3–6 days on average.

Understanding the Impact of Alcohol Dependence on Life Expectancy

At higher levels of use, the data is unequivocal. Alcohol dependence is associated with:

> Severe lifespan reduction (up to 28 years in some studies)

> Increased suicide risk

> Accelerated cognitive decline and neurodegeneration

> Higher rates of mitochondrial dysfunction

The dose-response curve is steep. Once regular heavy drinking begins, longevity declines rapidly. This is one area where the science is crystal clear, heavy drinking is incompatible with any serious longevity optimization strategy.

The Benefits of Recovery

Stopping or reducing alcohol consumption yields measurable benefits:

> Improved cardiovascular markers: Blood pressure and heart function often improve within weeks of cessation

> Better sleep and metabolic health: Many report dramatic improvements in sleep quality and metabolic function

> Reduced inflammation: Key inflammatory markers decrease with abstinence

> Slower biological aging trajectories: Some evidence suggests telomere rescue may be possible, though more research is needed

While some damage may be irreversible, recovery significantly improves healthspan and quality of life. For those looking to accelerate recovery, evidence-based interventions like heat therapy, cold therapy, and contrast therapy can support the body's natural healing processes.

The Lifestyle-Genetics Equation

When it comes to lifestyle versus genetics, alcohol is squarely in the "controllable" category. While some people carry genetic variants that affect alcohol metabolism (making them more or less susceptible to its effects), the decision to drink remains a modifiable lifestyle factor.

The research is clear: no amount of genetic advantage overcomes the biological damage caused by heavy alcohol consumption. And for those already optimizing diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management, alcohol may quietly erode those hard-won gains.

Final Perspective

Alcohol occupies a unique place in culture, tradition, and social life. But longevity science is increasingly clear: alcohol is not a health supplement.

Even moderate drinking appears to carry biological costs that accumulate over time. For those optimizing every other aspect of their health, from diet to exercise to sleep, alcohol may quietly erode hard-won gains.

Longevity is ultimately a series of tradeoffs. Understanding alcohol's true impact allows you to make those tradeoffs with open eyes, not comforting myths.

Looking for professional guidance? Browse our directory of longevity clinics and longevity doctors who can help you build an evidence-based health optimization strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does alcohol increase longevity?

No. Once bias is accounted for in research studies, alcohol does not extend lifespan. The supposed benefits of moderate drinking appear to be statistical artifacts related to the "sick quitter" effect and other confounding variables.

Why do whiskey drinkers seem to live longer?

Anecdotes and survivor bias. Population-level data does not support this claim. You're hearing from the people who survived, not the larger group who didn't.

Does alcohol shorten your lifespan?

Yes. Heavy drinking clearly does, and even moderate drinking may accelerate biological aging through telomere shortening and other mechanisms.

Is red wine good for longevity?

No. Resveratrol levels are too low to confer benefit at normal drinking amounts, and alcohol's harms outweigh any theoretical upside. If you want resveratrol, supplementation is a far more practical approach.

How much alcohol is safe to drink?

From a longevity standpoint, less is better. No amount improves lifespan, and even low consumption may carry small but measurable risks.

Does alcohol accelerate aging?

Yes. Multiple lines of evidence link alcohol to telomere shortening, increased epigenetic aging, and elevated biological age markers.

Can you reverse alcohol's effects on aging?

Some effects improve with abstinence, inflammation decreases, sleep improves, and metabolic markers often normalize. However, not all damage is reversible, particularly at the cellular level. The sooner you reduce or eliminate alcohol, the better your chances of minimizing long-term impact.

About the Author

Sign Up For Our Newsletter

Weekly insights into the future of longevity